Sherzad MamSani

President of the Israel–Kurdistan Alliance Network, EastMed Contributor

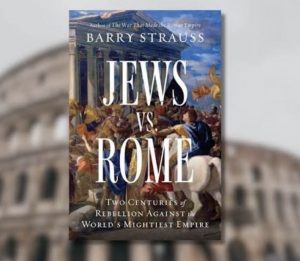

In his book Jews vs. Rome: Two Centuries of Rebellion Against the World’s Mightiest Empire, Barry Strauss draws a long-term narrative of a confrontation that spanned nearly two centuries between a small, deeply rooted people and the most powerful empire of its age—not as a single episode, but as a chain of political and military eruptions that ended in immense human catastrophe, displacement, enslavement, and the loss of political sovereignty.

This is not merely an (ancient story). It is a political laboratory for understanding a recurring mechanism: how a (permanent enemy) is manufactured when a great power fails to turn difference into obedience, or when elites need a scapegoat to justify violence and manage public anger.

The aim here is not a mechanical comparison between Rome and Israel, or between the Jews of Judea and the Jews of today. Rather, it is to trace the (political thread) that repeats across eras: when accountability of power is replaced by hatred of identity, criticism turns into an existential threat.

First: What Does Strauss Teach Us Politically About the (Logic of Empire)?

Strauss presents the Great Revolt, the Diaspora Revolt, and the Bar Kokhba Revolt as stations within a single arc: rebellion, suppression, punishment, and the re-engineering of political and social reality.

Within this arc, the (logic of empire) appears on three levels:

One, the security level. The empire does not see merely a political opponent, but a structural danger that must be uprooted. Thus, the language of (security) expands until it justifies policies that go beyond war into the dismantling of society itself.

Two, the symbolic level. It is not enough to defeat the opponent; their symbols must be broken. In the Jewish case, religion, ritual, the Temple, and the city become arenas of political humiliation as much as of war.

Three, the narrative level. Empires rule by the sword and by the story. They need a narrative claiming that repression is a (civilizational necessity), and that the other side is stubborn, extremist, or incapable of coexistence. This model makes it easier to transform an entire people into a (problem), not a society.

These layers matter because they are the same ones deployed today when politics is replaced by the stigmatization of identities.

Second: (Hatred of Israeli Governments) as a Mask — Where Does Criticism End and Hatred Begin?

The modern dilemma is not the existence of criticism of Israeli policies. Political criticism is normal in democracies. The problem arises when criticism shifts from policy to identity: (Jews) instead of (the government), (the Jew on the street) instead of (the political decision).

This is why different frameworks emerged to define boundaries. The IHRA definition describes antisemitism as a certain perception of Jews that may be expressed as hatred toward Jews and notes that it may target Jewish individuals, property, or religious institutions.

At the same time, the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism sought to clarify the distinction between antisemitism and criticism of Israel or Zionism, aiming to prevent the accusation from being used to silence political debate.

At the practical level, materials from organizations such as the ADL emphasize the importance of not automatically conflating criticism of Israel or advocacy for Palestinian rights with antisemitism. Even these institutions acknowledge that automatic conflation is a methodological error.

The conclusion is political rather than academic. Despite disagreements, there is a shared baseline:

Criticizing a decision, a government, an army, or a party is political criticism, however harsh.

Targeting Jews as Jews, holding Jews worldwide responsible for a government, threatening synagogues or schools, or questioning Jewish loyalty as a group is where antisemitism begins.

Third: The Most Dangerous Similarity Between Rome and Today Is Not Power, but (Excuses)

In the ancient narrative, Jews did not face Rome merely as a city, but as a system skilled at producing excuses. Every revolt became proof of (Jewish nature). Every incident became a verdict on an entire people.

The same logic appears today when the statement (I do not hate Jews, I hate the Israeli government) is followed by actions against Jews with no connection to political decisions: attacks on religious symbols, harassment of students, intimidation of communities, or discourse that reduces Jews to a state, a lobby, or an absolute evil.

This shift is not merely linguistic. It is functional. (Israel) becomes a password that allows socially rejected hatred to re-enter the public sphere under the guise of moral positioning. The individual Jew becomes a symbolic hostage in a conflict they do not control.

This is precisely what empires do, past and present. They blur the line between politics and identity to widen the circle of punishment.

Fourth: A Practical Test to Distinguish (State Criticism) from (Hatred of Jews)

Instead of getting lost in definitions, there is a practical political test.

First, is the criticism applicable to any other state. If the language and standards used are applied to no other country but Israel, one must ask why.

Second, does it assign collective responsibility to Jews worldwide. There is no democratic principle that holds a religious minority in Berlin or Paris responsible for a government in Jerusalem.

Third, does the discourse move from rights to incitement. There is a clear difference between advocating Palestinian rights and calling for harm, expulsion, humiliation, or threats against Jews or Jewish institutions.

Fourth, does it rely on historical stereotypes such as control, money, or dual loyalty. These are not political critiques but classic legacies of antisemitism.

Fifth: What Does the Comparison with Strauss Say About the Future of the Confrontation?

The harsh political lesson of the Roman story is not simply that Rome was stronger. It is that prolonged conflict produces two parallel outcomes: the resilience of identity even after state defeat, and the power of propaganda to turn victims into defendants over time.

Today, Jews do not face a military Rome, but something more fluid: a marketplace of narratives across media and platforms, where hatred is sold as moral virtue and human beings are reduced to slogans.

The core battle therefore becomes political and civic: protecting the public sphere from turning an external conflict into internal violence against communities.

Sixth: Political and Civic Recommendations (Not Slogans)

First, protect both rights: the right to criticize Israeli policies and the right of Jews to safety and full citizenship without fear.

Second, enforce the law decisively against attacks on synagogues and Jewish institutions, because this is not protest but a threat to the civil state itself.

Third, dismantle deliberate confusion: opposing a government does not grant the right to target Jews.

Fourth, reject moral blackmail: opposing antisemitism does not require endorsing every Israeli policy, and opposing Israeli policies does not legitimize hatred of Jews.

Strauss’s book reminds us that confrontation is not always between armies. Sometimes it is between a power that seeks to dissolve difference and an identity that refuses to be erased.

In our time, the greatest danger is turning the phrase (I hate the Israeli government) into a social ladder by which those who hate Jews can climb openly without consequence.